Listeners:

Top listeners:

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Electromusic FM RADIO ONLINE 24/7

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

London Calling Podcast Yana Bolder

Jaimie Branch’s final album with Fly or Die shows all she still had to give.

The revelation was delivered in a boxy, low-ceilinged cottage in a park in unhippest east Toronto. It was the spring of 2019, and my ears and expectations were fatigued from decades of too-frequent concertgoing. (An enforced protracted break a year later would alter things, but no one knew it yet.) In principle, a venue like this century-old lawn-bowling clubhouse halfway across town should have offered a hint of novelty. In practice, it was cramped, with harsh overhead lighting that washed out any speck of atmosphere. The elongated drones of the local opening guitar-and-drum duo, through no real fault of their own, had us nodding off in our folding chairs.

But then came Jaimie Branch, the trumpet player and vocalist from Chicago—or was it Brooklyn?—whom I’d read something about, but had never heard. She wasn’t putting up with any of this shit. As her bandmates in the quartet called Fly or Die testify in the liner notes of their latest album, out this week, “The environment in which the music would be performed was always as important as the art itself.” Branch snuffed out the overheads and scrounged up some kind of portable utility lighting. Now, in a small bright pool in the dark room, the effects pedals wired to her trumpet mic seemed like an array of occult accoutrements. We drew in closer like a ring of sorcerer’s apprentices.

Branch was outfitted like a Wu-Tang-style hip-hop shaman—in thick white sneakers, a backward baseball cap over rough-shorn hair, and a red-striped kimono draped around a short-statured figure that took up plenty of exuberant space—and was attended by the rest of her ensemble on bass, drums, and cello. I want to say she also had a megaphone, but I think it was just that she came across like a human bullhorn channeling an urgent directive from somewhere beyond.

“This is a song I wrote for America, and everything fucked-up that’s happening there,” she told us, introducing what would appear on that coming fall’s Fly or Die II: Bird Dogs of Paradise as “Prayer for Amerikkka Pt. 1 and 2.” It’s a song about asylum-seekers at the southern border, in part telling a true story about a teenage migrant that Branch had heard from her social-worker mother. Lest her Canadian audience feel too comfortably far from such horrors, she said she was sure we had our own versions. Which we do.

Then the rhythm section set up the groove, and Branch started blowing her horn, whose notes undulated, skyrocketed, and then dive-bombed again, like a dirt-streaked archangel leading a riot of the dispossessed to tear down the walls not just of Jericho but of all of the world’s borders. And for the following 90 minutes, that placid lawn-bowlers’ redoubt vanished around us, along with any jadedness in anyone’s ears or heart. By the end we were singing and clapping and howling as one along with both Branch’s half-sung, half-chanted lyrics and her most abstract-expressionist swaths of tone color. Like any really great concert, it was enough to make a person feel as if they’d never truly heard music before.

I doubt anyone in that room would have believed it if we had been told that within a few years this irresistible force would be gone. But on Aug. 22, 2022, Jaimie Branch died at home in Red Hook, Brooklyn, at the age of 39. Her family never announced a cause, though those aware of her past grappling with opioid addiction made our own sad speculations.

This loss was particularly jarring and sharp for the world of improvised music—as witness, this moving video of a procession to the docks of Red Hook by a host of New York musicians one month after her death. But it was a tragedy for every open-minded music lover no matter what their tastes.

There’s a reason I’ve avoided using the word jazz up to here, as Branch’s sound and vision couldn’t be constrained by the bounds of any genre, much less one so often misunderstood as fussy and moribund. Along with too many jazz figures to list, she also collaborated with indie-rock bands such as Spoon, Yo La Tengo, and TV on the Radio, noise bands like Wolf Eyes, the late Brazilian samba eminence Elza Soares, British dub producer the Bug, and the Indigenous music collective Medicine Singers. Earlier this year, she was featured posthumously on the latest album by Talib Kweli and Madlib.

Though Branch received both classical and jazz training at the New England Conservatory of Music, she came up as a composer and bandleader through the long-forged chains of connection between elders and newcomers in the creative music circles of Chicago. But she also shared her generation’s collective debt to rap culture, which you could not only see in her personal style but hear in her speech and her music, which was unusually groove-friendly for avant-jazz. She played in ska and punk bands starting in high school, and punk attitude and the subculture’s DIY ethic radiated off her skin.

That mélange, along with Branch’s personal magnetism, helped make her music accessible to many listeners who aren’t initially inclined to seek out jazz. In this she was a peer to such celebrated young artists as London’s Shabaka Hutchings (Sons of Kemet) and Nubya Garcia, its soul collective Sault, California’s Kamasi Washington and Thundercat, and Philadelphia’s Moor Mother and Irreversible Entanglements, whose bassist Luke Stewart was a frequent Branch collaborator.

While the mostly acoustic Fly or Die group was Branch’s best-known project, much of her time more recently had been devoted to electronic music, including on three albums with Anteloper (her synth duo with drummer Jason Nazary) and in performances with the trio C’est Trois. No matter where she went stylistically, though, her personality shone through, with a distinct mix of up-for-anything energy, an aching compassion for the world’s travails, and anger at the forces behind them—approached with a spiritual awareness inherited from the Black lineage of free jazz—as well as an underlying, rawly vulnerable and sweet hopefulness.

Branch hadn’t always been at ease letting that side of herself out. As she told the music site Aquarium Drunkard in 2019, “For me, there was an emotional part to improvised music that I was not so keen on leaning into at first, because I thought it was corny or cheesy or something like that. Like playing a simple melody is probably not something I would have done in 2007 or 2008.”

But on her path in the 2000s—which she began as a prodigy surrounded by expectations—she was waylaid by the worst of her addiction, which left her seeming to be almost a late bloomer instead. She dropped out of a graduate program at Towson University in 2014, later remarking that Baltimore wasn’t the ideal place to live if you were trying to quit heroin.

After going through rehab in 2015, sponsored by the Recording Academy’s MusiCares program, she ran out of patience with playing coy. She required a more direct line to meaning and stakes. “When I’m up there,” she said in that Aquarium Drunkard interview, “I’m putting it all out on the table. It’s like high risk, high reward. … I want them to know that I mean every note that I play.”

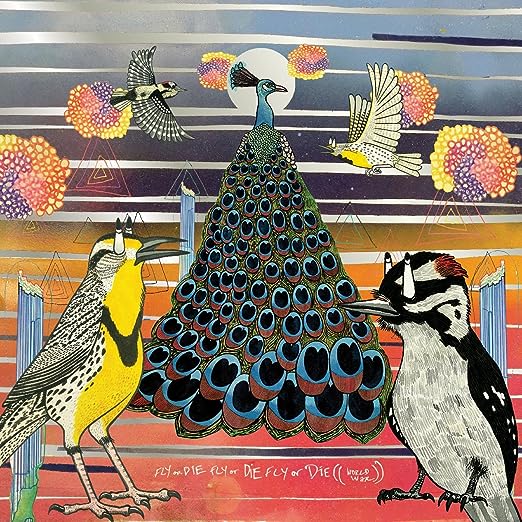

That commitment is unmissable in all the Fly or Die material, which brought her acclaim and live audiences around the world. That group had two studio albums during her lifetime, plus a live collection. This week brings a final installment, at least the last one that Branch was able to personally oversee through to mixing last summer before her death. As the third in the trilogy, she called it Fly or Die Fly or Die Fly or Die ((World War)). Branch herself, incidentally, would have spelled this and her song titles—as well as her own name—all in lowercase, in protest against what she half-jokingly called “capitalist letters.”

The new album opens with a kind of secular baroque organ hymn in “Aurora Rising,” followed by the luminous jazz overture “Borealis Dancing.” But it really begins to take off with the first track featuring lyrics (about half the songs, for the first time), a snaking nine-minute punk conga line called “Burning Grey,” which includes the chant, wrenching in context, “I wish I had the time, I wish I had the time, I had the time/ I had the time of my life,” but also implores the listener: “Trust me, just for a moment/ Believe me, the future lives inside us/ Don’t forget to fight, don’t forget to fight.” Then there’s a sudden swerve in the direction of Appalachia in the next track, “The Mountain,” where the vocals are led by bassist Jason Ajemian and the lyrics and melody come from 1990s Arizona band the Meat Puppets’ psychedelic punk hoedown “Comin’ Down.” (You may or may not recall that Nirvana, a lifelong Branch favorite, covered three Meat Puppets songs on the MTV Unplugged album.)

Another album highlight is one of Branch’s pieces nodding to her Latin American heritage (Colombian on her mother’s side), “Baba Louie.” Besides featuring some of Branch’s most beguiling trumpet lines and standout rhythms from her extraordinary drummer Chad Taylor and guest percussionists, it includes a sudden citation from Cuban folk anthem “Guantanamera.” This links it into the lineage of protest music (perhaps you’ve sung along with Pete Seeger’s version) as well as reminds us that the original is about a woman from Guantanamo, a reference that’s acquired some new connotations in the 21st century.

Later, Branch’s punk roots are exposed in the rapid-fire exclamations of “Take Over the World”—on my shortlist of the best singles of 2023 so far—and proceedings are brought to a menacingly quiet close with the electronic pulses and chimes (courtesy of the disturbingly cheerful vintage toy the Happy Apple) of “World War ((Reprise)).”

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

As a whole, this suite’s effects may not be quite as concentrated as on Fly or Die II, which was a high-pressure artifact of the Trump years. But as a travelogue through so many of her galaxies of sound, it attests to the grand dimensions of Branch’s capabilities and, heartbreakingly, all she could have done next.

Besides that sense of loss, listeners might take away for themselves Branch’s sense of how much could be built, through collective improvisation, from the smallest of ideas and possibilities. “I’m listening big all the time and making strong decisions,” she told jazz writer Phil Freeman in 2019. By paying close enough attention in the initial moment of creation, she said, the artists could find a way to “split that up into a million things” and move forward.

In many ways, it marks the difference between mere jamming and something closer to intuitive composition. “Even though we’re improvising,” Branch said, “we’re playing this music right here. So let’s really try to figure out what this music is, even if it’s in the moment … flesh it out by whatever means possible.”

Even if all you have is a utility light and a kimono.

Written by: Soft FM Radio Staff

album Branchs Die final Fly Give Jaimie shows

Similar posts

Electro Music Newsletter

Don't miss a beat

Sign up for the latest electronic news and special deals

EMAIL ADDRESS*

By signing up, you understand and agree that your data will be collected and used subject to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Podcast episodes

Invalid license, for more info click here

Invalid license, for more info click here

Copy rights Soft FM Radio.