Listeners:

Top listeners:

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Electromusic FM RADIO ONLINE 24/7

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

London Calling Podcast Yana Bolder

MTV had gotten serious. A Red Hot Chili Peppers music video showed us the dark underbelly of sunny Los Angeles, under the bridge. R.E.M. took us inside the minds of people stuck in traffic to show why everybody hurt. Van Halen scrawled warnings onto the screen: “Right now, justice is being perverted in a court of law”; “oil companies and old men are in charge.” Every few hours, Pearl Jam staged a grunge opera of adolescent tragedy. Even Garth Brooks caught the mood, donning a fake beard to play a wife-beating sociopath in “The Thunder Rolls.”

Then, in the middle of 1993, came the most serious music video of them all: “Runaway Train” by Soul Asylum, newcomers to MTV. Between shots of a scruffy-looking band performing in a derelict farmhouse, a parade of horrors threatened America’s children. A white-haired man enticed a boy with candy. A dour-looking girl in adult makeup approached cars in a seedy parking lot. A woman frantically scooped a baby out of a stroller and ran.

Intercut were names and photos of actual young people labeled missing, most of them prime MTV age.

As “Runaway Train” rose up the charts, the director cut two additional versions with different names and photos, provided by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, to increase the number of kids seen by MTV and VH1 viewers. In total, 36 from the U.S. were put on screen. (This approach was replicated for British and Australian music video channels.) And on Aug. 10, 1993, the Associated Press reported that a 16-year-old girl, who had absconded two years prior with her boyfriend, saw herself on MTV and called her mom. She was back under her family’s roof in Arkansas, studying for a GED and planning for college. NCMEC’s president told the AP that five others from the video had reestablished contact with their families. The narrative was clear: The video worked.

By the end of 1993, Soul Asylum had already sold more than a million copies of Grave Dancers Union, the album on which “Runaway Train” appeared. In 1994 the introspective ballad won the Grammy for Best Rock Song. Today the song has 250 million streams on Spotify, and the video has 200 million views on YouTube, where nine of those kids are frozen in perpetuity, in one of the three versions.

“Runaway Train” is still remembered for its video, and for reuniting missing children with their families. In 2019 NCMEC revived the video for “Runaway Train 25,” a cover of the song with an updated music video. This one geographically tracked the viewer to show them cases of missing kids close to them. Publicity materials for the campaign asserted, “25 years ago, one music video helped recover 21 missing children,” a claim that was repeated in the press. This was also the recollection of the director, Tony Kaye: In 2022 he told the Guardian that, of the 36 kids featured in the U.S. versions, “we eventually found 21.” He added, “I’d argue it was the single most important thing that happened in the history of MTV, because it saved young people’s lives.”

—

Director Tony Kaye

Eleven kids from the U.S. videos are still missing. Four were ruled dead. That leaves 21 “found.” But only that one case, from the 1993 AP story, was ever documented. She was also the only “Runaway Train” kid who appeared in an Access Hollywood segment on the 30th anniversary this summer.

As that milestone approached—and amid a new panic about missing and exploited kids that in some ways mirrors the one from the “Runaway Train” era—I wondered: What really happened to those kids? Before the video, and after? I tried to track down all 21 of them, now in their 40s. Several agreed to speak with me. All were determined runaways and none of them said they were “saved” by the video.

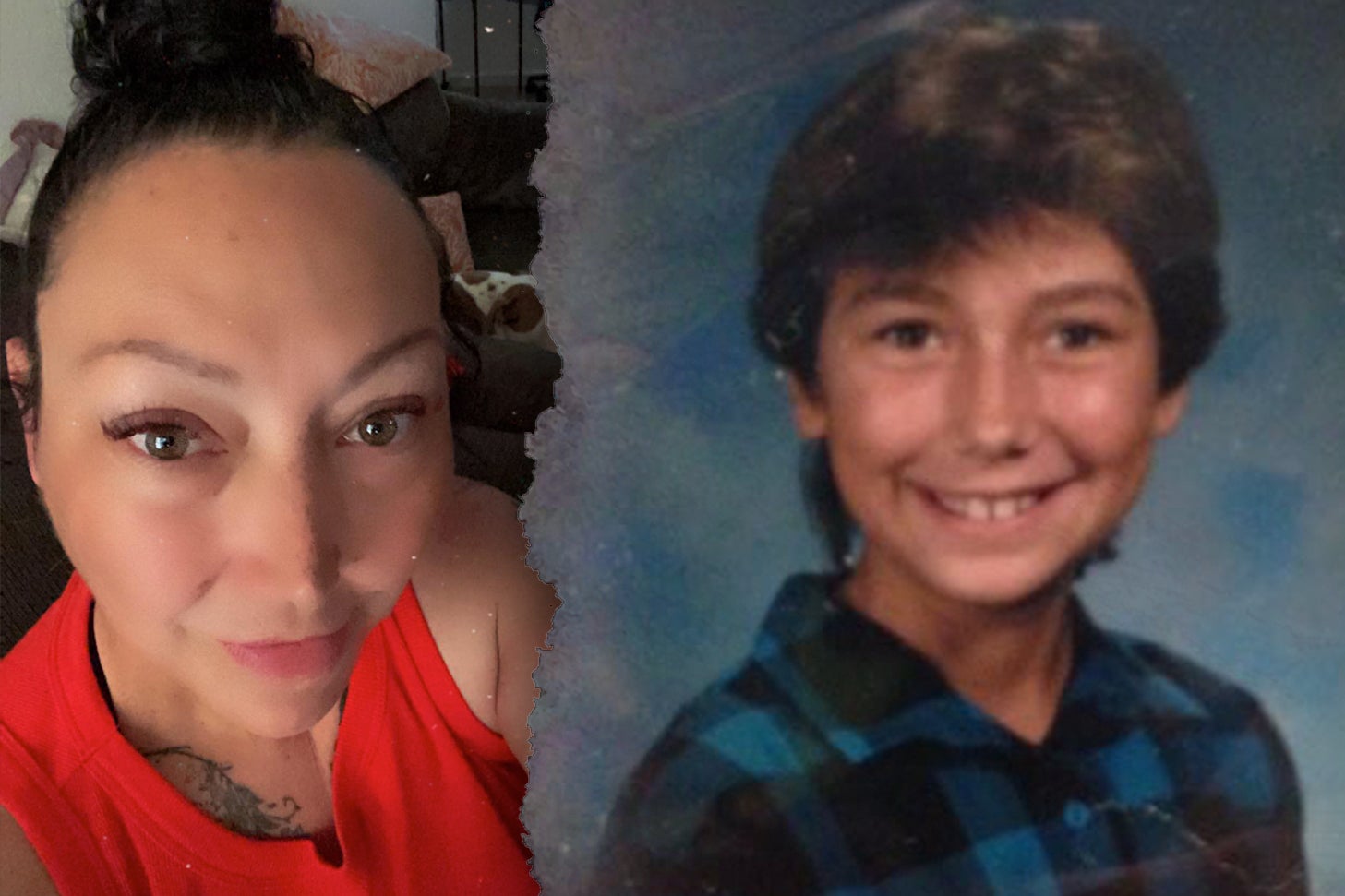

“When I see it, I’m like, You gotta be kidding me. Like, what the hell?” recalled Joyce Collier, a “Runaway Train” kid who is now 47. “In my case,” Collier told me, “I guess I didn’t want to be found until I was ready to be found.”

These reactions were not uncommon among “Runaway Train” kids. A public panic over “missing” or “lost” youth overshadowed the complicated truths behind those pictures. I also found that some members of the band discovered that reality for themselves. Guitarist Dan Murphy said he remembered a girl with sandy-blond hair walking up to the band at a meet-and-greet and asking, “Why are you fuckers trying to ruin my life?”

“Runaway Train,” the song, was never about runaway kids. Lyrically, it is about an all-consuming and nonspecific bleakness, about getting in too deep and feeling as if there’s no way out, of traveling only through a cycle of depression.

Dave Pirner, Soul Asylum’s lead singer and main songwriter, wrote it at the band’s lowest point. Soul Asylum had been dropped from A&M Records after releasing two albums to little notice. And Pirner thought he was losing his hearing after 10 years playing small, loud clubs as a punk and alternative-rock band.

“I was just very inconsolable,” Pirner said in an interview. “I was in a downward spiral. I didn’t know much about anything as far as what was going to happen to me and what was happening in my life. I mean, the whole prospect of believing that you’re going deaf, and you make music for a living, was insane.”

It forced him to write on an acoustic guitar for the first time. He took inspiration from Woody Guthrie. Guthrie wrote a lot of songs about trains. The end result was a song perfectly engineered to chug up the early-’90s charts. “Runaway Train” echoed the social alienation that was characteristic of grunge but also had a verse-chorus-verse simplicity and a melodic shine that meant that it wouldn’t scare radio stations that played Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty. It would be right at home on both the youth-oriented MTV and the more adult-oriented VH1.

On the strength of a demo that included “Runaway Train,” Soul Asylum signed to one of the world’s biggest record companies, Columbia.

Pirner’s hearing healed with some care and safety precautions; he started carrying earplugs. The band, at the time, was him, Murphy, bassist Karl Mueller (who died in 2005), and drummer Grant Young (who was on his way out).

Grave Dancers Union came out in October 1992. Columbia released two other singles that got airplay on college and alternative radio. After six months, the label still hadn’t released “Runaway Train,” its ace in the hole.

It would need a video. The band had never had much interest in making them. A&M had paid for some clips, but they were always low-budget. “We didn’t have much control at all,” Murphy said. “We show up for a day, listen to whatever the director tells you to do. And then you’d see your video and you either absolutely hated it or you thought it was OK.”

Columbia sent Pirner some VHS tapes of director reels. “I came across Tony Kaye’s tape,” he said, “and I thought it was beautiful-looking.”

Kaye had directed some award-winning TV commercials in his native United Kingdom. Music was often integral. Pets cuddled by the fire to the Shirelles’ “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” in an ad for a fuel company. The Velvet Underground’s “Venus in Furs” throbbed to hallucinatory imagery of body paint and bondage masks to sell car tires. Kaye naturally graduated to music videos.

Kaye was also intense. He came to Los Angeles in 1990 and, by his own recollection, thought of himself as a potential Francis Ford Coppola or Orson Welles. When a studio eventually hired him to direct a feature film, 1998’s neo-Nazi drama American History X, it ended in an epic, public fight over creative control that made Kaye almost unemployable at major studios. But that all came later.

Murphy remembers “just an incredibly charming guy, British and kind of dressed like Oscar Wilde.”

Over a lunch in Los Angeles, Kaye pitched Pirner his idea. He started talking about milk-carton kids. Pirner didn’t follow.

“And then he said, ‘Yeah, and then we’re gonna try to find them,’ ” Pirner recalled. “And it just clicked. I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ So, even though he was just making a word association with the word runaway, which really has no bearing on what the song is about, I was thinking, Hey, this could be interesting.” (Representatives for Kaye did not respond to detailed requests for comment.)

To a band apathetic about music videos, it seemed like a good use of the record company’s $100,000. “It felt pretty good to have a video that was something other than just a promotional tool for the band and had meaning and had reach,” Pirner said.

The song swept the band from clubs to amphitheaters. “Runaway Train” even did great on pop radio. In August 1993, it became the second-most-played song on Top 40 stations in the U.S. And because of the video, the band came to be known as the guys rescuing runaway kids—even by the president of the United States.

On Sept. 14, 1993, Soul Asylum, apparently a favorite of then-13-year-old Chelsea Clinton, played in a tent on the South Lawn of the White House to mark the signing of a new National Service Act. Staffers in business attire awkwardly tapped their feet. When Tabitha Soren of MTV News asked the president, “Why Soul Asylum?” Clinton responded, “They made that wonderful song about runaway children, which had a big impact on young people throughout the country.”

That fall, Soul Asylum co-headlined the MTV Alternative Nation Tour, the network’s answer to Lollapalooza. It was on this tour that Murphy remembers the sandy-haired girl asking him, “Why are you fuckers trying to ruin my life?”

He doesn’t remember her name and thinks she was being semi-sarcastic. Almost all encounters back then were a blur, as the band was constantly being scuttled around, but she made it clear: She was in the video, and she had left on her own. “I don’t think, at that point, she had considered herself to be a runaway, you know?”

It was the first time he realized that the people in the video might have a very different perception of it than their parents and the NCMEC.

Most of the youth who were in the “Runaway Train” videos are now middle-aged adults, spread across the U.S., many with marriages, families, and careers. They are sometimes the subjects of speculation on true crime forums and subreddits.

Some did not return messages seeking interviews for this story. A few politely declined. But several spoke to me about how they ended up labeled missing and the moment, during a time of deep turmoil, they saw themselves on MTV.

Joyce Collier was born in 1976 in Cleveland. When her father died, she told me, she was responsible for two younger siblings. “I never got to be a kid because I was raising my brother and sister when I was younger, and then my mom had this boyfriend that was a crackpot.”

When he started sexually abusing her, she ran away, hiding out with the help of a boyfriend her family didn’t know about. She was 15.

She became pregnant. She said it happened the first time she had sex with her boyfriend. During the pregnancy, her boyfriend’s family sheltered her in the nearby city of Parma.

She wanted to get her GED and go to college, but first, she felt, she had to stay under the radar until she was 18. For one thing, she was afraid her mother would force her to give up her daughter, putting her up for adoption or foster care. “I kind of just stayed away from Cleveland, stayed in Parma, did my little own thing, took care of my daughter, and that was it,” she said.

The “Runaway Train” video was a shock. She remembers driving a friend to a job at a restaurant. Another employee there said she recognized her from a music video. She went home and turned on MTV. Eventually, she saw her school photo.

At age 18, she presented herself at a Parma police station to shed her missing status. Her mother had to come to confirm her identity. When her brother ran and hugged her, their mother scolded him. That was a stranger, she said. We don’t talk to strangers. Their relationship was forever strained.

After she turned 18, Collier continued to stay with her boyfriend’s family. Each day, she dropped her daughter off at day care and walked to GED classes. She passed and then took classes for nursing but never completed the degree. She had two more kids and bounced from job to job.

She now lives in Sumter, South Carolina, and, for the first time in her life, has no one else to care for.

“Now that my kids are grown, it’s just like, I just do what I want,” she said. “I get up when I want. I sell stuff online, so I work from home. It’s amazing, and I wouldn’t change anything.”

Ginger Vila was born Ginger Hudson in 1975. When she was a teenager, raised by a single mom in Denver, she developed a severe fear of crowds. With individuals, she was fine, but larger groups of people were debilitating.

“My social anxiety was so bad,” she said. “I didn’t want to be around people. My mom and my brother didn’t understand.” She decided to run away from home to escape having to go to school.

Vila described this time in her life to me matter-of-factly while shopping for groceries and occasionally responding to her 9-year-old daughter.

At 16, she entered into a pact with a friend to secure his immigration status. She could stay with his sister in Las Vegas until she turned 18 and then they would get married so he could apply for a green card. She got on a bus to Vegas, but the sister backed out when Ginger’s mom got wind of it.

On a Greyhound, as she was returning to Denver, another vagabond suggested she go to a truck stop and hitch rides. So she did. After a few months of riding around highways, she met the man she would call her boyfriend.

He lived in his truck and, when he wasn’t driving, parked it at a dispatch center in California. She stayed with him. It wasn’t bad for someone with a kind of social anxiety that allowed her to hitchhike fearlessly but paralyzed her when she went to school or a mall.

She cozied up in the truck when he was away. “I would stay in the pickup truck for hours,” she said. “Then I would go to a restaurant to use the restroom and then go buy food and then go back. It was better for me than being out there alone.”

He was 35, with a daughter only a year and a half younger than her. “I don’t think he was a predator,” Vila said. “He probably thought I was over 18.”

The man’s daughter first spotted Ginger in “Runaway Train.” The daughter then kept watch over MTV and recorded it on a VCR, which is how Ginger saw it.

Like Joyce Collier, she was laying low until she turned 18. As unconventional as her life was, it seemed to soothe her social anxiety. They laughed off the video. She rarely went anywhere besides the truck. Who would recognize her?

She turned 18 and reestablished contact with her mother, but she remained in California. She scoured newspapers for work-from-home jobs. Many turned out to be scams. She and the trucker rented an apartment but broke up in 1999.

Hudson now lives under one roof with her daughter, her daughter’s father, and her current boyfriend. Antidepressants have stabilized her, she said.

Maybe, at 16, she could have stayed home, she said, if she’d had access to medication or home-schooling. But she didn’t, so she doesn’t regret leaving. “I felt like I had no choice,” she said.

Jessica Molnar, born Jessica Williams in 1975, said she “never had a dad.” She remembers only a succession of her mother’s partners. At 16, she decided to abandon her “toxic” household. “I would have hurt her husband or myself,” she said.

She took a bus from Colorado Springs, Colorado, to Dallas. There, she had a friend with a place where she could stay, plus a connection who made fake IDs. The ID helped Jessica get a job at a burger joint, and then one at Walmart, and she saved enough to get her own apartment.

She remembers seeing the video. She was agitated. “I don’t like people knowing my business,” she said.

Also, crucially, she wasn’t missing anymore: She turned 18 in the fall of 1993, and she had called her mother to reestablish contact before she saw the video.

Over the years, Molnar earned a high school diploma, got married, had two children, got divorced, had another kid, and adopted her brother’s two biological children. She now lives in Oklahoma City. She worked for the Head Start program for 20 years and now works for a cannabis dispensary.

She’s never regretted leaving. As she put it: “I left to break cycles, and I did.”

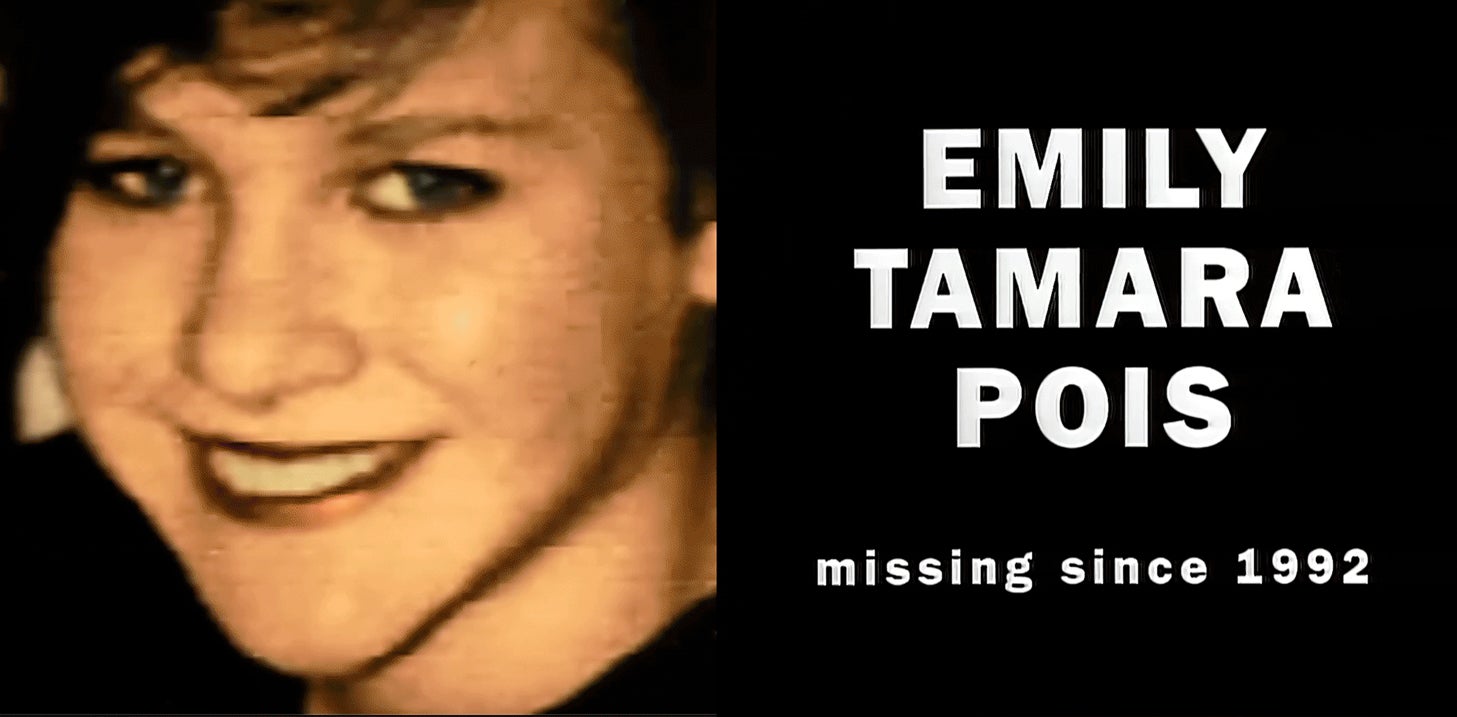

Emily Pois did not understand why her classmates found her weird. Years later, Pois, born in 1978, was diagnosed with Asperger’s. As a kid in Boulder, Colorado, all she knew was that she had been singled out to tease.

At the start of adolescence, she discovered Boulder’s punk scene. It was full of kids who also didn’t fit in at school or home. Some were transient and managed to stay out of the reach of parents. She thought she could live like that.

She said her father and mother “were great parents.” They were both even-tempered college professors and provided an upper-middle-class home. She had two half sisters she liked. “It was just, I didn’t fit in,” she said. So she ran away often.

At age 13, she got on a Greyhound to San Francisco. There was a community of punk kids there, though that term didn’t necessarily mean spiked hair and black leather jackets. In San Francisco, punk meant banding together to survive within the cracks of society, mostly homeless and jobless. “The cops had better things to do than go after homeless kids,” Pois recalled.

She checked in with her parents regularly. “They just wanted to know that I was alive and everything,” she said. They didn’t pressure her to come home. “I think they were scared that if they did that, that I wouldn’t contact them anymore.”

At 15, she relocated to Minneapolis, where friends had an apartment where she could crash. It was the regional punk scene that, a decade earlier, begat Soul Asylum.

They were not sure how, but the apartment got cable, Pois said. They were all hanging out with MTV on, and she suddenly saw her picture in the video. She pointed it out to her friends. They all laughed.

But Pois was actually nervous. Minneapolis cops were more hands-on about runaway kids, and this could mark her.

“That just gave me a sense of dread,” she said, “because I was expecting to get fucked with a lot more after that.” But she was never recognized from the video.

Soon, the city punk scene took a turn. It was infiltrated by angry men in their early 20s. Some drank and used drugs. “Bad things started happening, and people started getting a lot more cutthroat,” Pois said. “People were ripping each other off. It was funny to do mean shit to your friends.”

It was this kind of cruelty that spurred her to run away in the first place, so at 17, she went home.

Then, her life really took a turn for the worse. She obtained her GED and took classes at a community college, but in quick succession, her father died, and an early marriage ended in divorce. “My life since then has been a series of periods of being clean and periods of being addicted to drugs,” she said.

When she’s sober, she works in kitchens. But when she relapses, she’s all in. “I pretty much lost my mind for, like, three years,” she said. In 2015 her family reported her missing again.

Now she is stable, she said, and is working as a coordinator in a hotel kitchen and doing peer support for other people in recovery.

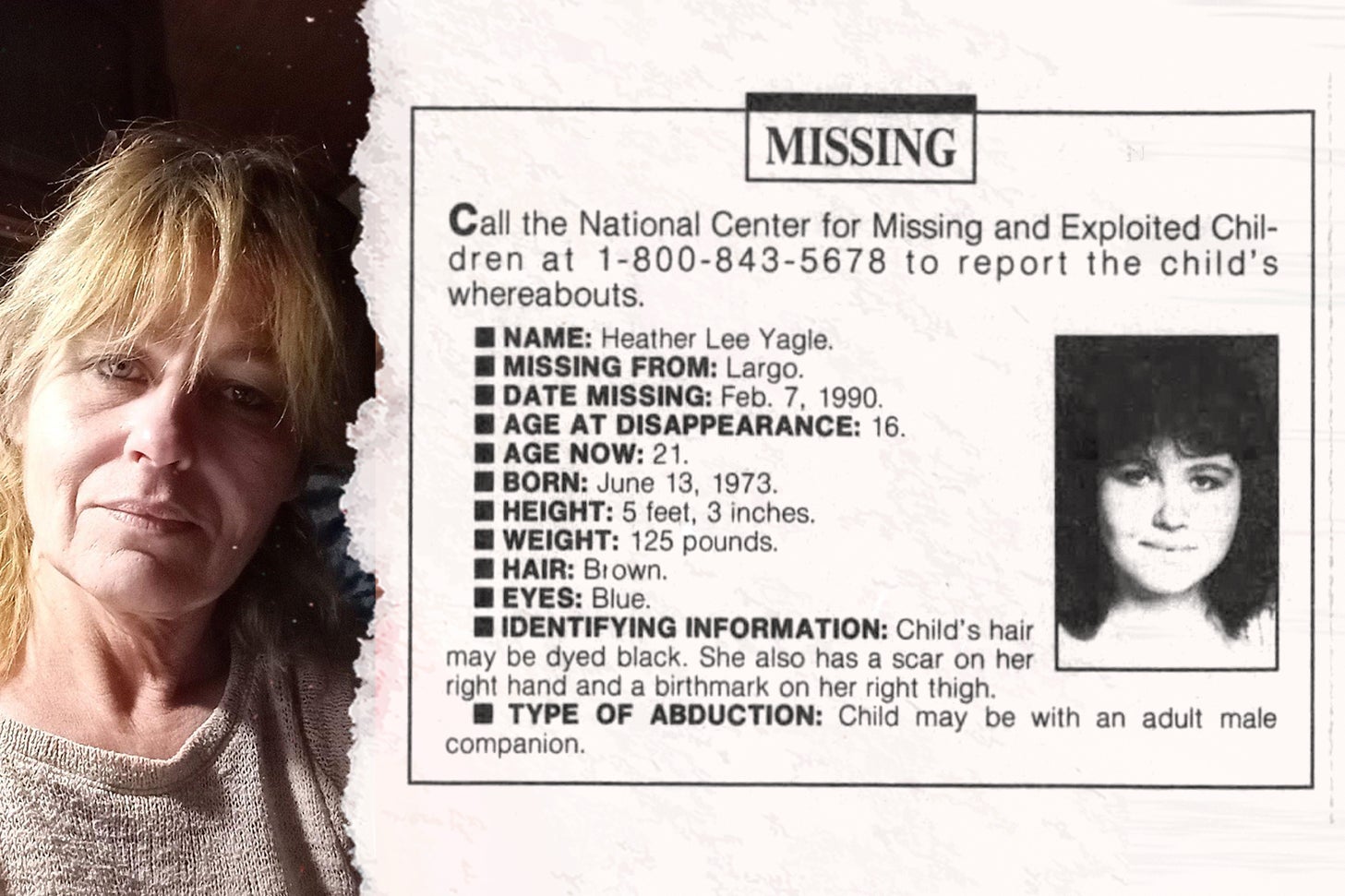

Heather Yagle said her last memory of her father is of federal agents hauling her away from him. Her parents had fought over her. Not a custody battle—she remembers being physically between them as they tussled. Her father got a hold of her and drove her to a Seminole reservation in Florida. He was a member of the tribe. Days later, FBI agents came to retrieve her.

The next few years were harsh. She and her mother traveled around a few states, homeless. Her mother met another man. He was initially in their life long enough to impregnate her mother and sexually abuse Yagle when she was 5, she told me. Her mother went into labor when they were squatting in an abandoned building.

There was a brief period of stability after her mother married another man, a stepfather to both her and her brother. They settled in Largo, Florida. One day, she picked up the phone, and on the other end was the voice of the man who had molested her.

“I come to find out my mom had been talking to him for, like, two years prior to that,” she said. She had told her mother about the abuse. Her mother didn’t believe her. Yagle felt betrayed. Soon, her mother and stepfather were fighting about her mother’s ongoing contact with the other man.

Yagle made a few attempts to run away. After one, the FBI found her again and escorted her back to her mother.

When Yagle turned 16, a neighborhood friend, Steven, offered to help. Steven had lost his fiancée in a car accident. He was 25, and he and Yagle bonded over their traumas. Though they were not, at that time, in a romantic relationship, the two fled to West Virginia, where 16-year-olds could (and still can) get married, which, Steven thought, would make him her legal guardian.

After getting married, they roamed around a coal-mining county with few prospects or connections and wound up homeless. Police rounded them up. They put Yagle on a plane back to Florida.

Steven followed her and they ran away again, this time to a rural Mississippi town where Yagle still lives. They found an arrangement where they helped manage an apartment complex in exchange for their own apartment. Three years went by. Then, a tenant approached her and asked if she was a runaway.

“I was like, ‘Oh, what’re you talking about?’ and he says, ‘I’ve seen you on MTV.’ ”

She watched MTV for two days, she said, and eventually saw the video. It was her ninth grade yearbook picture, a bad one where her mother had attempted to curl her hair.

“I was in shock,” she said. Yagle was 20 and didn’t know that her mother was still looking for her. She called NCMEC to ask why she was in the video. The operator pleaded with her to contact her family.

Before the end of 1993, TV interceded again. Yagle got a call from the producers of The Jerry Springer Show. Her mother had signed on for an episode of reunions between parents and runaway children.

Springer was new and had not yet gone all in on in-studio fistfights. It still kind of resembled Oprah or Donahue. “I ended up calling her because I had to make a decision if I wanted to be on the show,” Yagle said. They talked for a long time, surprisingly, exchanging bits about their lives while dodging the issues of why she ran away.

She went to Chicago and reunited with her mother and brother on Springer. Yagle remembers it fondly and has searched for a tape of it. The segment would be the only time they were all together during her young adulthood.

Though her mother and stepfather had stayed together, her brother’s dad was in the family’s lives. “So I stayed away,” Yagle said. “I spoke with my mom on the phone several times throughout the years. But technically I never really went back, because it was still the same problem.” It still felt to Yagle as if her mother had picked her abuser over her.

Yagle’s associations with Springer and the “Runaway Train” video make for fun facts to tell new acquaintances, and she thinks of the video as the start of a series of events that allowed her to have a relationship with her mom, who has since died. On her phone, the ring tone for her mother used to be “Runaway Train.”

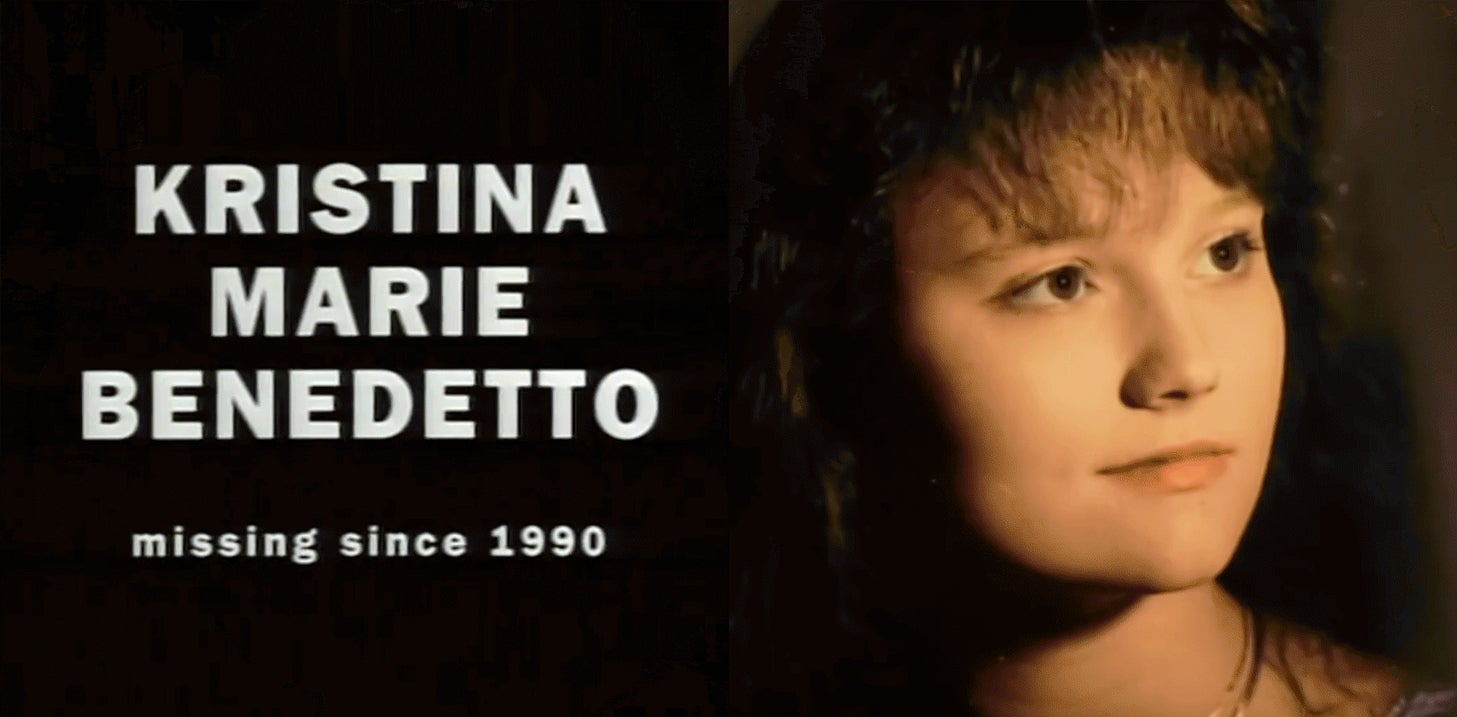

At least two “Runaway Train” kids died years after the video aired. Kristina Benedetto was one of them. In 2019 she drowned in a hot tub on a property in Sonoma County, California, where she lived. It was an accident. She had epilepsy, and her brother, Vincent Frank, thinks the drowning was probably preceded by a seizure. She was 44.

Though Benedetto is no longer around, Frank, her half brother, was willing to tell me her story. Some of it may seem, by now, familiar. He told me that in 1987, his father, also named Vincent Frank, was convicted of attempted sexual assault of Kristina, an account that matches information in the California Sex Offender Registry. Kristina was 12. He went to prison, but the family dynamics soured, and at age 15, she ran away. According to Frank, the “Runaway Train” video was “one of the reasons she called my mom to reconnect” a few years later, but this wasn’t till after she had turned 18.

The “Runaway Train” video was an experiment, a music video meant not just to influence music or fashion or CD sales or the band’s image but to directly influence the lives of 36 people.

Neither Pirner nor Murphy has paid much mind to the video’s “success” rate, which seems to have been tallied by NCMEC for “Runaway Train 25.” In an interview, a NCMEC spokesperson seemed to walk this back and said, “We don’t know it was because of the video, but 21 of those cases were resolved.”

Pirner, who still heads Soul Asylum, said he is proud of calling attention to child safety, but as for the details, he isn’t very involved. “Those numbers fluctuate wildly, and I did not review 21 cases to make sure. We hear things. It’s a lot of speculation on something that’s tragic and personal.”

Even back in 1993, the band started to dodge the topic, said Murphy, who left Soul Asylum in 2012.

“That was something that none of us were comfortable talking about in interviews at that time either,” he said. “I remember that was kind of a joke: ‘How many kids did you guys save?’ We heard that a lot. But I didn’t get that involved with the specifics.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to view the video as a product of its time. The tactic it used had been a familiar one. Starting in 1984, the dairy industry had plastered photos of missing kids on billions of milk cartons. Ronald Reagan had coaxed newspapers to print them as a “mission of mercy,” and after NBC aired a TV movie about the murder of Adam Walsh that premiered to 38 million viewers, the president appeared in a prerecorded message to personally introduce a list of names of missing children.

The moral panic over abducted children, spurred by rare but high-profile cases, had morphed into one about “lost youth.” Photos like these were spread far and wide to enlist the general public as a rescue force against whatever terror awaited them on “the streets.” Research has since shown that child abusers are rarely strangers but, in more than 90 percent of cases, someone the child knows. Even among the four “Runaway Train” kids who were ruled dead, three of their cases were resolved, all of them with the conviction of a family member or someone close to the family.

“Runaway Train” begins with the sound of sirens and the text “There are over 1 million youth lost on the streets of America.” The statistic seems to be a rounding up of the FBI’s count of 800,000 children under the age of 18 reported missing in 1992. By the bureau’s own estimation, only 200 to 300 of those children were taken by strangers, a category that accounts for a fraction of a percent of missing-children cases.

Many of the statistics—and much of the news coverage—conflated runaways, children taken amid custody disputes, incidents when parents briefly lost track of a child, and stranger kidnappings, lumping them into one big, scary category, according to Paul Renfro, a professor of history at Florida State University and the author of Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State.

“There’s this idea ‘missing children,’ just as a term, becomes synonymous with this seeming epidemic” of abductions, he said. A missing child was presumed kidnapped.

The specter of kidnapping still haunts Pirner, especially now that he’s a father. “You’re always looking over your shoulder when you got a little one, and having someone snatch that kid away is devastating to me,” he said. “I can’t even, like, imagine how awful that would be. It is also important to make a distinction between kids that are abducted and kids who run away.”

Renfro said that following decades of social upheaval, this amorphous “missing child” narrative colored news reports, the anxieties of parents, and pushes for tough-on-crime laws into the 1990s and beyond. “There are kids ‘on the streets,’ right? And that’s juxtaposed to ‘the home,’ and ‘the home’ is always good or usually good, and perhaps some family situations and domestic situations are not ideal, but the place where the child should be is the home.”

The actual lives of “Runaway Train” kids were more complicated. They ran from sexual molestation, cycles of abuse, and school days that filled them with dread. Some, impressively, found stability. It wasn’t always by coming home.

Written by: Soft FM Radio Staff

Asylums Kids music save Soul video

Similar posts

Electro Music Newsletter

Don't miss a beat

Sign up for the latest electronic news and special deals

EMAIL ADDRESS*

By signing up, you understand and agree that your data will be collected and used subject to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Podcast episodes

Invalid license, for more info click here

Invalid license, for more info click here

Copy rights Soft FM Radio.